Chambal: a name synonymous with outlaws, ravines, and a history as wild as its landscape. But beyond the legends, what lies within this infamous valley? I ventured into the heart of India’s dacoit country to find out.

- The Dacoit Legacy

- The Agra Car Rally: A Journey Through Rural Uttar Pradesh

- Historical Context: Dacoits and British Rule

- Tales of the Outlaws

- Bateshwar: Shiva Temple and History

- Shauripur: Jain Temples and Spiritual Encounters

- Chambal River: The Elusive Safari

- Planning Your Trip to Chambal

- Best Time to Visit Chambal

- How to Reach Chambal Valley: Travel Tips and Routes

The Dacoit Legacy

‘Kitne aadmi they’, ‘Yeh haath humein de de Thakur’, Gabbar Singh roared in the iconic film Sholay (1975). The rocky terrain, the ravines, the wilderness…we were biting our nails. Horses, guns, masks, coarse language, sleazy expressions (especially on the ‘Mehbooba’ song), dark clothing and cruelty incarnate—we were transported to the dark world of fearsome, lawless dacoits.

(Kitne aadmi they–how many men were there?, Yeh haath humein de de Thakur–give me these hands Thakur)

The thrill of going to Chambal, India’s renowned dacoit valley, was to catch a glimpse of this reel-life or real-life human being just once. Thankfully, this didn’t come to life on my trip. But some rewinds would be good, like going to explore this valley properly, especially for the Chambal gharial safari and stay at the hunter’s lodge.

If you are a Millennial, Gen Z or Alpha, late actor Amjad Khan’s character, Gabbar Singh, was inspired by the dacoit culture prevalent in the Chambal region, possibly modelled on the notorious Gabbar Singh Gujjar.

From the days of the British Raj till the early 2000s, Chambal, a region encompassing belts of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, was home to terrorizing dacoit gangs. The most famous being Nirbhay Singh Gujjar, Man Singh (Lion of Chambal), Malkhan Singh Rajpoot (Bandit King), Putlibai (female dacoit known as Bandit Queen), Kallu Yadav aka Kalua (Katri King), Mohar Singh Gurjar, Nizam Lohar, Daaku Madho Singh, Chhidda Makhan. Some were viewed as Robin Hoods, others as plain criminals. But all were outlaws.

The Agra Car Rally: A Journey Through Rural Uttar Pradesh

Let’s jump to February 2015. The occasion was Agra Car Rally, hosted by Uttar Pradesh Tourism. Green mustard fields, stark landscape, a blue sky and thrilling drive, the road from Etawah to Agra, via Chambal, was an introduction to the lesser explored interiors of Uttar Pradesh.

Rustic, old-world, and poor, this India lives in mud homes. Earthen stoves are lit by cow dung, camels carry the load, and not many people own a bicycle. The small clusters of houses marked the various villages that we crossed on this dusty drive.

Unfazed by the attention, we stopped to click selfies in mustard fields, scaring the peacocks. We marvelled on seeing a real well from which the villagers drew water.

Chambal’s landscape is thorny, bushes of wild berries growing along the roadside. What were once hills, were now mud banks. The government, helped by nature, turned most of it into agricultural land.

Historical Context: Dacoits and British Rule

It’s unclear how the region became the centre for dacoits, probably hardship, caste system, greed, illiteracy and rebellion against the British. It’s difficult to narrow down the cause. However, the British did try to counter this with the ‘Thuggee and Dacoity Suppression Acts’.

They introduced the Acts in 1836 through several legislative measures, establishing special courts, authorization for using rewards for informants, and the power to arrest suspects. Remember the Aamir Khan-Amitabh Bachchan starrer, Thugs of Hindostan (2018), now I understand the thought.

The “Thuggee and Dacoity Suppression Acts” primarily targeted the Thuggee cult, but also addressed the issue of dacoity in the region.

Interestingly, the word dacoit stems from the Hindi word ‘Daku’. It is also listed in the Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases (1903).

Tales of the Outlaws

Curious about the region’s notorious past, we egged our driver for information and stories. Luckily, he was forthcoming. He recounted tales of some famous ones—Nirbhaya Gujjar, Phoolan Devi, Paan Singh Tomar. The dacoits actually did not like to trouble the villagers much but being an outlaw was the answer to oppression in those days.

Nirbhaya Gujjar, who died in November 2005, was the local Robin Hood. He ruled for 31 long years, terrorizing the rich and helping the poor.

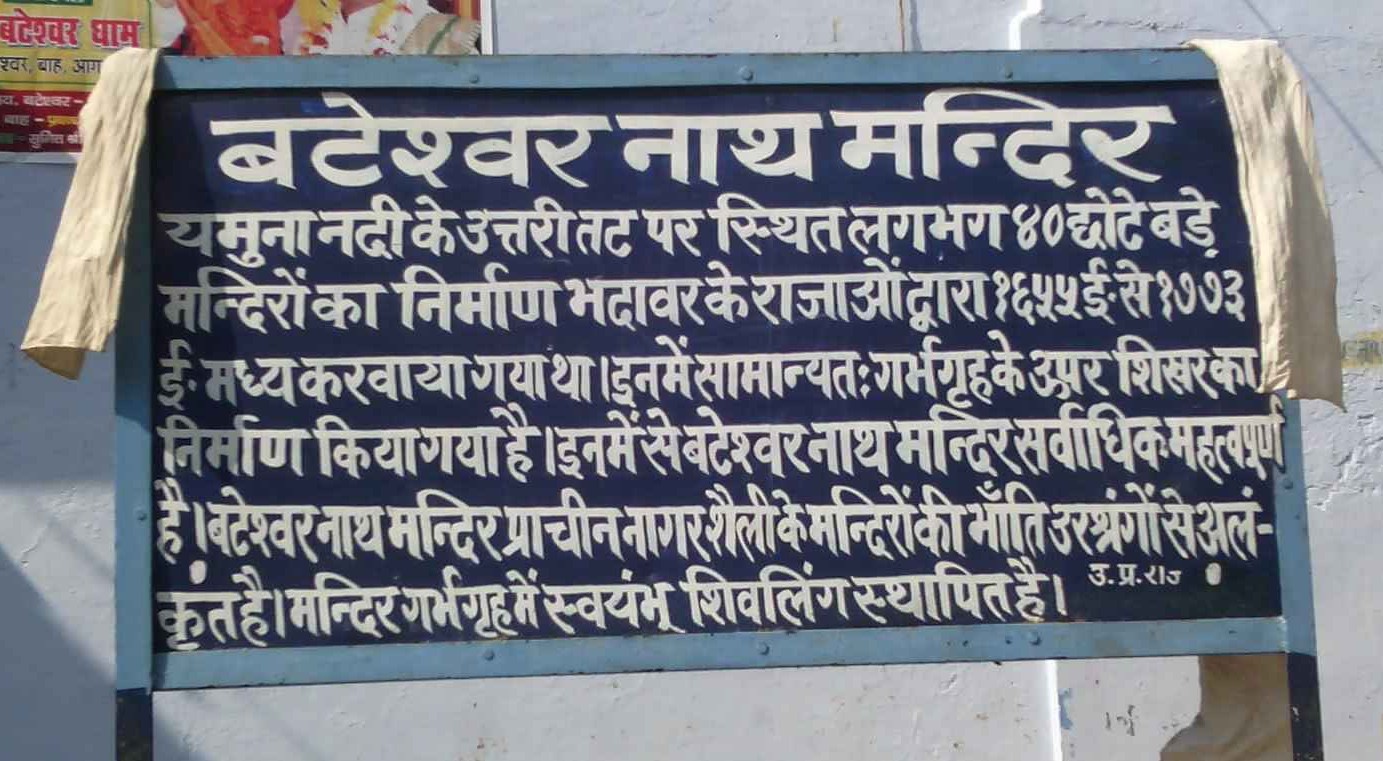

Bateshwar: Shiva Temple and History

The tales would have continued, but the car rally went over a precarious pontoon bridge, forcing us to halt the conversation. With bated breath, we waited our turn as only one car could cross at a time.

Then, our media car diverted and wound its way to a famous Shiva temple in Bateshwar. The village is also the ancestral home of late prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. He and his elder brother Prem were arrested at Bateshwar on August27, 1942, for 23 days during the Quit India movement.

A long time ago, a wider Yamuna River flowed behind the temple which houses 101 shivalingas. According to legend, Shiva rested under a vat or banyan tree here, giving rise to the name Bateshwar, the banyan lord. The temple was built by Raja Badan Singh Bhadauria (1655-1773).

Now the narrower Yamuna had few boats and some water birds. Graceful swans glided across the water, while goats baahed and trotted alongside us as we attempted to capture the scene through our lens. A small kingfisher perched on an electrical wire. To think I saw this then, and I wasn’t even a birdwatcher. But then, I feel I missed the real biodiversity, which I would enjoy now. And I had just started to use my mobile as a camera, which means I really relied on my brain power and not visual senses to reconstruct this travelogue.

Bateshwar is also the spot for the 2nd largest annual cattle fair in India.

Shauripur: Jain Temples and Spiritual Encounters

The next stop was a famous Jain temple in Shauripur, just 3 km from Bateshwar. This village is believed to be the home of Lord Krishna’s ancestors.

Amid serene greens, no one could pinpoint exactly when this old Shauripur-Bateshwar Jain temple was built. With less footfall, it retained its positive energy, the perfect spot for a yogi and tired city hearts.

The temple is dedicated to the 22nd Jain Tirthankar, Lord Neminath. Touted as his birthplace, Lord Neminath was Lord Krishna’s cousin.

It is widely believed that Lord Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara who revitalized Jainism, also stayed at Shauripur at one time. The temple houses idols of Lord Mahavira—one in the traditional sitting posture and the other standing.

Greeted graciously by the priest residing there, we walked barefoot to witness the silence of divinity. The idols are special as they are said to have the mark of the tirthankaras.

The priest pointed out a snake’s shadow in the black stone statue of Lord Mahavira in the seated position. We watched this shadow from all directions, trying to figure out whether it was the play of sun or some supernatural phenomenon. It could be an optical illusion caused by the lighting and the statue’s features.

Then he took us to the second idol, pointing out the conch and lotus flower in the God’s chest and navel. We were left bewildered by these strange shadows. The songs of birds seemed surreal as well.

Chambal River: The Elusive Safari

From the unexplained to the visual…the drive took us to the Chambal River. The peaceful riverside belied the legacy of curses, revenge and dacoits. Legend says that this is the river besides which the Pandavas and Kauravas played a dice game on its banks, resulting in Draupadi’s humiliation. She cursed the river, vowing that anyone who drank from its waters would suffer from an insatiable thirst for vengeance.

Another legend states that the river sprang from the blood of countless cows sacrificed by King Rantideva in his quest for absolute power, some say that the cows approached him for salvation. It was originally known as Charmanwati River.

While fear, distrust and dry land drove humans away, biodiversity thrived. The curse has helped the Chambal to survive unpolluted by man, and its many animal inhabitants to thrive relatively untouched.

Our plan was to embark on the famed Chambal Safari to spot the gharials. The National Chambal Sanctuary, stretching across Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh, is home to endangered species like the gharial (a fish-eating crocodile), the elusive Gangetic dolphin, and a spectacular variety of birds.

Alas, this safari didn’t take place, as we were in the wrong spot. The state department boats which had a permit for this safari, started from another point.

Disappointed, we collected some shells from the river shore, talked to the young girls tending sheep. A rustic boat ferry carrying people and their vehicle—motorcycle and bicycles–was crossing the river. In a daring feat, I saw a man holding his bicycle on one side, hanging precariously over the water. The ride from one shore to the other cost INR 10.

After a picnic under a huge peepal tree, we stopped in the ravine for some dacoit-like shots, sans the guns and horses. And joined the car rally at its last stop in Agra.

Planning Your Trip to Chambal

It is good to plan your trip ahead of time, especially if you want to take part in activities like the Chambal River safari.

While the Chambal region has become much safer, it’s always advisable to be cautious and aware of your surroundings.

Take a trusted guide.

Wear muted clothes. Carry less luggage, only the basics, and food and water as well.

Carry your first-aid kit and other emergency tools such as power banks.

Keep your phones and cameras charged.

Best Time to Visit Chambal

The ideal time to visit Chambal Valley is between October and March, when the weather is pleasant, and wildlife sightings are at their peak. The migratory birds grace the region, making it an unforgettable experience for photographers and travellers alike.

How to Reach Chambal Valley: Travel Tips and Routes

- By Air: The nearest airport is Agra (approx. 70 km), well-connected to major Indian cities.

- By Rail: Dholpur and Agra railway stations provide easy access.

- By Road: Well-connected highways make Chambal Valley accessible from Delhi, Jaipur, and Agra.

I’m participating in #BlogchatterA2Z

Recommended Reading

A: Chandigarh Rock Garden Concern: Why Public Art Matters

B: Bhimtal: The Emerald Beauty in Uttarakhand

As elaborate as you usually are! Wonderful post. I particularly loved that pic of a house which seems to be cut into a rock.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know why you liked it–it’s rebellious! :P The house is actually cut into a thick mud hill, I hope it has lasted till now.

LikeLike